Beware of spoilers throughout the text.

You will have to forgive me for the flurry of posts and a sudden surge of activity on this blog – a) I need to create a modest library of a few posts to support the newly created blog b) It’s almost Christmas time and I fully intend to make the most use of the coming Christmas holidays to watch quality cinema and read quality books. As always, I am more than happy to share my thoughts with you on this.

So, La Haine (Hate) is probably one of the most critically acclaimed movies of all time – in fact, if a connoisseur of French cinema is to come up with a list of the best French films of all time, you should be wary of just how knowledgeable they are if they don’t have La Haine on the list. If a bunch of aliens were to land tomorrow on our planet and ask just one full-feature film to understand the human condition, we need little more than La Haine. The young director Matthieu Kassovitz was only 29 years old when he directed this masterpiece – at about the same age, you would find me yapping about movies of such calibre in 2500 words or fewer. For all its acclaim and universal love, this film is simply about three young French immigrants hanging out and killing time in the French suburbs. Greatness is in simplicity.

The film is set in the Parisian suburb (or more correctly, banlieue) of Chanteloup-les-Vignes, where years of civil discontent and disillusionment, simmering long under the surface, have erupted into a boil when the police brutality during the riots injured and almost killed a young French-Arab immigrant Abdel Ichaha (a fictional person inspired by the many victims of police mistreatment and abuse). In fact, Kassovitz dedicates the film to all those who died while the film was being made, presumably victims of similar circumstances. The banlieue is La France Moche (The Ugly France) in all its glory – an urban hell with its tenement buildings, decay, crime and poverty, sequestered safely away from the rich and developed downtown Paris metropolitan area with its beautiful Palais de Justice, old churches, lawns and the attendant bullshit.

The film is entirely in black and white to underscore just how much hopelessness and gloom pervades the immigrant French suburbs of the 90s, situated firmly on the wrong side of the social divide. Graffiti replete with ”F*ck the police” messages grace many a brick and metal pane in the background. In an atmosphere of much fraternité and very little égalité, three friends of Abdel, Vinz (Vincent Kassel), Hubert (Hubert Koundé) and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), have-nots of Jewish, African and Arab descent, respectively, are seen dealing with an aftermath of a fierce bout of riots. In fact, Vinz is baying for blood, itching for an opportunity to stick it to the man and to answer violence with violence. The atmosphere in the cité itself is akin to a powder keg, with the slightest of insults being capable of triggering massive retaliation on both sides, with the police being nervously vigilant for the tiniest bit of provocation.

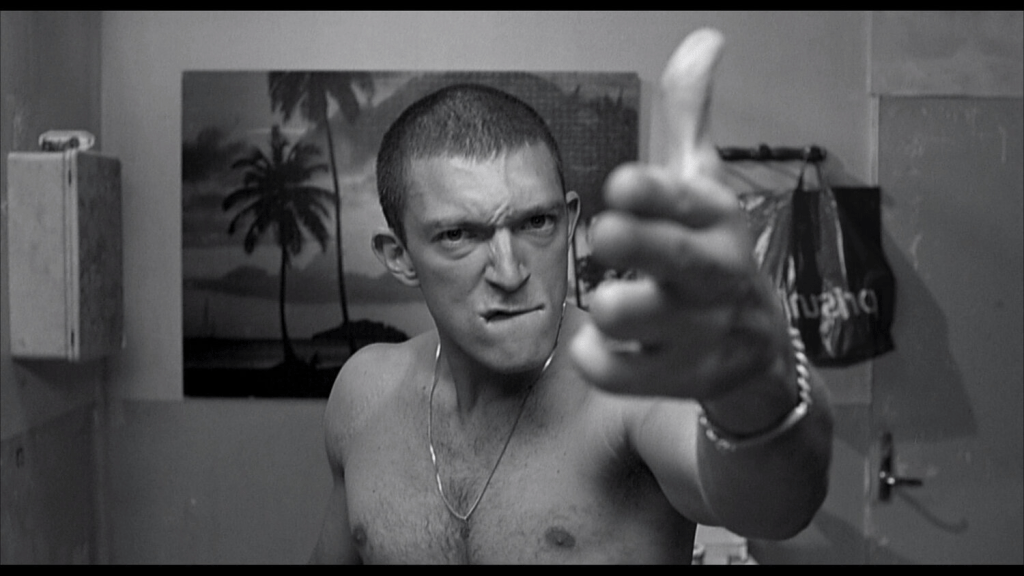

War and strife take their toll – Hubert, a boxer, has his boxing gym burned down amid riots, and his dreams of escaping the slums are evaporating by the second. Hubert is acutely aware of the destructive nature of hate, having witnessed the ugliness descend and spiral further until no one remembers who is at fault anymore. In fact, the movie borrows its name from the line said by Hubert to Vinz ”La haine attire la haine – Hate begets hate”. Vinz is stubbornly refusing to listen, but what would you expect from someone whose morning routine is to emulate Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver – Dir. Martin Scorcese) in front of his bathroom mirror? In fact, Vinz has found a gun dropped by an incompetent young police officer the night before and is all too keen to administer some old-fashioned Smith and Wesson justice. The revolver plays a classic Chekhov role in the story with Vinz flashing it at almost any opportunity in an effort to inflate his own non-existent role in the society that never needed him.

In one of the best scenes of modern cinema, Vinz, Saïd and Hubert are having a tense conversation in the stalls of the public bathroom. Vinz is tired of being a cog in the broken and unfair system and feels that refusing to turn the other cheek is the best practical way to buck the system and exert meaningful change. Hubert is tired, too, but he refuses to indulge in Vinz’s blood-for-blood, tit-for-tat strategy of killing a policeman should Abdel succumb. Saïd is caught trying to haplessly mediate the fiery temper of Vinz and an equally cold and assertive sternness of the humanist Hubert. In the middle of an intense argument, out comes a short and stocky man from the bathroom stall, presumably a Jewish rabbi (I could be wrong), and states with Zen-like clarity to the speechless trio: ”Nothing like a good shit!”.

The old man, the follower of Hashem (again, presumably), gives a beautiful monologue to the youth. I can’t help but reproduce the monologue here in its entirety:

”Do you believe in God? That’s the wrong question. Does God believe in us? I once had a friend called Grunwalski. We were sent to Siberia together. When you go to a Siberian work camp, you travel in a cattle car. You roll across icy steppes for days, without seeing a soul. You huddle to keep warm. But it’s hard to relieve yourself, to take a shit, you can’t do it on the train, and the only time the train stops is to take on water for the locomotive. But Grunwalski was shy, even when we bathed together, he got upset. I used to kid him about it. So, the train stops and everyone jumps out to shit on the tracks. I teased Grunwalski so much, that he went off on his own. The train starts moving, so everyone jumps on, but it waits for nobody. Grunwalski had a problem: he’d gone behind a bush, and was still shitting. So I see him come out from behind the bush, holding up his pants with his hands. He tries to catch up. I hold out my hand, but each time he reaches for it he lets go of his pants and they drop to his ankles. He pulls them up, starts running again, but they fall back down, when he reaches for me.”

When Saïd asks ”Then what happened?”, the old man responds with ”Nothing… Grunwalski froze to death. Goodbye”.

Plenty to dissect here. First of all, how come, with all their contemptuous disregard for authority, the friends never interrupt the old man? The friends despise the notion that to the rich and powerful, the wretches in the lower circles of social hell are nothing more than a faceless mass, eating away at all the succour generously provided to them by the elite. The old man is not one of the elite – in fact, he is one of them, a former victim of either the Stalinist purges or the Nazi Holocaust, probably with a tattoo of a number on his wrist. More so, the old man gave the friends something they rarely get and so desperately want from the system – being heard. The rabbi, all while emptying his bowels, absorbed and processed the gist of the argument, and engaged in a meaningful dialogue with the youth, never mind the fact that the meaning eluded all three of them. I could be wrong – the old man seemed all too gleeful recounting the morbid story, so, perhaps, there was no dialogue at all and the old man enjoys telling the story pathologically to anyone he meets while taking a dump.

More importantly, what does the story mean? Ask ten people and you will likely get ten opinions. In fact, something tells me that this is precisely what Kassovitz wanted. In my view, this message of the story is easily summarized by one of the best doctors on screen, the beloved acerbic Dr. Gregory House (House M.D.):

” I don’t care if you can walk, see, wipe your own ass… [dying] is always ugly – ALWAYS! You can live with dignity; we can’t die with it!

Yep, sometimes you either have to decide between living with your pants down and genitals exposed, or dying with your dignity intact. Sure, you may have your legitimate grievances, but are you willing to give them up to foster peace? Or is your own self-righteousness more important to you, contributing to the divide? Vinz’s unrelenting stance of ACAB is keeping the hatred swirling and churning in his soul. Buddha said that holding on to anger is like drinking poison and expecting the other person to die. It doesn’t matter if your anger is well-earned – you are still bearing the brunt of the suffering the more you hold on to it. Making peace and admitting defeat often feels like dropping pants metaphorically – where have you lost your balls? – but it’s precisely what’s needed to halt the circle of violence and hate. I may very much misinterpreting Kassovitz’s message, but if that’s what he intended to communicate, I can’t say I agree. An impetus is always needed to initiate change in society, except the change can’t be shooting up a random cop on the street. Since violence and inequality are the only things these guys have known since birth, it’s the only solution that Vinz’s feverish mind can arrive at.

My own view parallels that of Hubert, as a matter of fact, possibly consigning me and thinkers like Hubert to a similar fate. Expatiating about making peace sounds cool, but, like Hubert, it is difficult for us to escape the gravitational pull of blood for blood. Hubert is a hypocrite, but whereas Vinz is an idealistic extremist, Hubert is a nihilist. In the early scenes, you are led to believe that Hubert is the only force capable of assuaging and mollifying Vinz’s wrath lest he descend into a fit of murderous, psychopathic frenzy. However, Hubert, also having descended from the gutter, is much more comfortable with violence than he is willing to admit. He differs from Vinz in that he believes systemic change is impossible, and maybe some cops are even good, so why bother shedding blood? It’s better to run and never come back.

The movie’s final scenes bring Hubert’s hypocrisy into sharp focus. After being stranded in downtown Paris thanks to some plainclothes policemen and missing the last train at the Saint-Lazare station, the group commits a bunch of petty crimes, first to try and get back home, and then to kill time until morning arrives. Hubert and Saïd are ambushed by a bunch of skinheads and would have been beaten badly had Vinz not arrived promptly with his revolver to bolster his authority. The group manages to capture a single skinhead (the other cowardly dogs run away), and it’s Vinz’s prime time to actually walk the walk and put a bullet into the base of someone’s skull. After all the bullshit machismo Said and Hubert had to listen to, Vinz better live up to his fiery rhetoric. Hubert is egging him on ”The only good skinhead is a dead one”.

Vinz can’t do it. It’s one thing to talk of wanting to kill someone, and the other to feel the cold steel of the gun handle, your face covered in sweat as you are about to stare some poor sucker right in the eye and wipe them off the face of the Earth, with their hopes, dreams, aspirations, their memories of being tucked into bed by Mom in childhood, their feelings of sadness at the first unrequited love in early adolescence, their resolve to change life for the better, every good and bad thing they had ever done. Hubert is no stranger to death, I presume, so he knows the only way to dissuade Vinz from killing someone is to give him an actual chance to pull the trigger. Yet, Vinz’s weapon is the anti-Chekhov gun – it’s a prominent part of the story, yet at the last moment, Vinz falters. I feel for Vinz – he isn’t hateful, just in pain.

You might think that I am ignoring Saïd in all of this. In every movie shot, Saïd is shown either between or to the side of Hubert and Vinz. He never openly agrees or disagrees with either Hubert or Vinz, but is always caught in the middle. Both Hubert and Vinz interpret the Grunwalski story differently, and Saïd is the only one without a genuine interpretation of the meaning of the story. Saïd is an observer – the movie begins with him opening his eyes and in the end, closing them. This underscores the circular nature of the loop of violence, letting us believe that the film is set in its own version of hell you cannot escape from, since the class lines are forever hardened and those destined to suffer will suffer for eternity.

This trick reminded me of Infernal Affairs (2002 – Dir. Andrew Lau, Alan Mak), a crime drama set in 1990s Hong Kong, with the clock displaying the same time both at the beginning and the end of the movie. Keen viewers have taken this to interpret that the movie is set in Avici, one of the lowest levels of twenty-eight Buddhist hells (Naraka). Avici can be translated as ”interminable” or ”incessant” where sinners suffer without the possibility of respite. Only through exhaustion of your bad karma can you escape. All our three heroes don’t seem to have a job or be preoccupied with anything else – their entire life, entire existence is the banlieue. Vinz’s death at the hands of the cop at the very end is an exculpation of his sins – he paid off his karma by renouncing violence, and in the end, is free from La Haine.

In the end, Vinz truly gets it. You can live for something or you can die for it. Vinz hands off the gun to Hubert in a moment of genuine repentance and growth of his character. If we are living on this planet to learn lessons assigned to us by the divine curriculum, it’s natural that our lives end once we learn them. A bunch of cops that Vinz previously disrespected pull up in front of Vinz and Saïd. The cop’s gun accidentally discharges. Vinz falls on the cold ground. Rest easy, it’s finally over.

Despite his moralizing, it is Hubert who ends up pointing the gun at the cop who had just shot Vinz. The cop aims back at Hubert. The battle lines are finally drawn, and you have to pull the trigger. The nature of violence in society is almost reflexive. It’s Newton’s third law – for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Hubert does not want to kill, but he has to. It’s not up to him anymore. Violence is circular. The ending is ambiguous – it’s not clear whether the cop pulls the trigger or Hubert or both. It doesn’t matter. Turn on the evening news, and it’s all just a statistic.

Kassovitz makes his point with a story in both the opening and closing scenes of the movie. The story is narrated by Hubert. It goes like this:

”Have you heard about the guy who fell off a skyscraper? On his way down past each floor, he kept saying to reassure himself: ‘So far so good… so far so good… so far so good.’ How you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land.”

That’s how we fend off the uncomfortable idea that our society is a sick one. I am not the one hurt, so so far, so good, I guess. As our society is plummeting further and further into moral depravity, it’s soothing to repeat the ”so far, so good” mantra. The problem is that after every free fall, comes the landing part. The pain you feel after the landing is indicative of the wrongs we’ve been methodically sweeping under the rug. We are all Saïd, so we close our eyes, hoping it will all go away. Ostriches bury their head in the sand – in doing so, I can only assume that predators disappear. After all, ostriches as a species aren’t considered threatened.

This movie is perhaps way too appropriate now in light of Luigi Mangione’s recent fatal shooting of the United Healthcare CEO, Brian Thompson, and his subsequent detainment by the NYPD soon thereafter. I wish I could give some clever, astute social commentary, but I don’t have much left to say about this anymore. You know, Jusqu’ici tout va bien… (So far, so good…).

Addendum: This movie opened up to me a whole new world of old-school French rap of the 90s.